Is Japan's Semiconductor Market Lighting Up?

The resurgence of interest in Japan's semiconductor industrial policy is a result of both recent legislation intended to support the long-term expansion of the US semiconductor manufacturing industry and the potential for new alliances to fortify supply chains and counter China's strategic challenges.

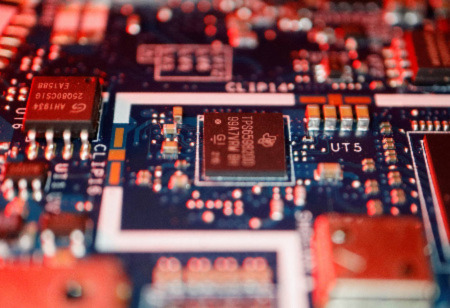

Although complicated, the semiconductor manufacturing process can be roughly separated into the front-end and back-end. Semiconductor circuits are manufactured on silicon wafers during the front-end process. The silicon wafers are divided into chips in the back-end process, which involves mounting the chips on metal frames before wiring and encasing them.

Many Japanese firms are excellent at generating the components needed for the back-end procedure and putting together semiconductor devices.

Looking at its history, the semiconductor industry can be divided into three phases: the rise of Japanese semiconductor companies from the 1970s to the 1980s, their gradual decline from the 1990s to the 2000s, and a period of renewed national attention paid to its semiconductor industry from the 2000s to the present.

A Smooth Phase: 1970 - 1980

During the 1960s to the 1980s, Japan gradually increased its global market share in semiconductor manufacturing and other sectors of the semiconductor industry, such as chip design, materials, and manufacturing equipment. The government made attempts to promote Japan as a leader across all domains of the chip sector, coinciding with a huge surge in domestic demand for semiconductors used in consumer devices. According to sources, the 1970s and 1980s were a period of international competitiveness and success for the Japanese semiconductor industry, thanks to a surge in private investment.

Japanese industrial policy aided semiconductor companies in increasing their global market share. Significantly, funding for research and development (R&D) in semiconductor production equipment increased to 26 percent of overall R&D spending in Japan in 1977, up from two percent at the start of the 1970s.

In addition, the Japanese government contributed $300 million in 1976 to establish the Super LSI Technology Research Association, a public-private collaborative technology research project with Japan's six major computer companies: Fujitsu, Hitachi, NEC, Mitsubishi Electric, NTT, and Toshiba.

Stumble Blocks: 1990 - 2000

As Japan entered an era of economic dynamism in the 1970s, policymakers in the US began to perceive Japan as a growing market competitor. With growing unhappiness in the US with perceived unfair trade practices by Japanese business, the US began pressing the Japanese government for trade concessions. Concerned about being locked out of the US market totally, the Japanese made concessions under the US-Japan Semiconductor Accord in 1986.

The deal provided the US the ability to set minimum fair market prices for chips in the US, while also expanding foreign share of the Japanese semiconductor sector from 10 percent to 20 percent. These two requirements weakened Japanese competitiveness in both the global and domestic semiconductor markets.

During the late 1990s, most countries' main business model for the semiconductor sector had shifted away from vertically integrated corporations that created and manufactured semiconductors and toward highly specialized firms that designed or manufactured chips. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), the first 'pure-play' foundry company created in 1987, paved the way for the industry's specialization.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the Japanese government launched many initiatives to encourage companies to specialize, saying that enterprises should reduce their duplicative investment in manufacturing infrastructure and redirect their spare capacity to enhancing high-value design capabilities.

There were also a number of government initiatives aimed at advancing Japanese leadership in the design and manufacturing of future generations of smaller and more advanced semiconductors.

Nevertheless, many Japanese semiconductor companies were unable or unwilling to react to new global industry trends. One of the reasons Japanese semiconductor businesses lost their competitiveness was that sales of digital products in Japan were stagnant, which meant that they had less resources to engage in R&D operations. Firms were disincentivized from divesting from any of their high-revenue departments since they had less capital to invest.

However, while the Japanese government's support of joint initiatives was originally beneficial to the semiconductor industry, it gradually reduced diversity among Japanese semiconductor manufacturers due to standardization of technology and leveling of technology among their companies. As a result, the industrial structure became one that made it difficult for companies to react to changes in the competitive environment.

Smoothing the Rough Edges from the 2000s

In response to Japan's semiconductor sector's relative downturn, the Japanese government has deepened its efforts to steer the country's semiconductor industry toward a more globally competitive business model.

Today, industry observers are already speculating as to whether these firms, which have lagged in producing sophisticated semiconductors, will be able to grow their market share.

Japanese companies have lagged behind in front-end technologies, specifically the capacity to transcribe fine circuits on silicon wafers.

On the other hand, several of the country's companies are world leaders in related materials and production equipment.

High-speed semiconductors are essential for automated driving and the expansion of 6G, the next generation standard for high-speed, high-capacity telecommunications, but companies are reaching the limitations of what they can do to better advanced products through finer and finer circuits. There is now hope that 3D stacking of chips in the back-end process will provide a solution.

In 2021, Resonac and 11 other related companies formed Joint2, a corporate collaboration to collaborate on 3D technology development. In addition, the government will provide them with up to $5 billion in assistance. For the first time, a section of the venue at last year's Semicon Japan, an international semiconductor exhibition, was dedicated to the back-end process.